By Whitney Clavin | December 16th, 2019

About 16 years ago I was ecstatic to hear I got the job as a science communicator at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), with the specific task of covering the upcoming launch of the Spitzer Space Telescope. My background was not in space, but biochemistry. I had worked in a lab in New York City for five years, researching the molecular happenings of various yeast genes, and had subsequently earned a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. My first post-graduate school job involved writing about molecular biology for The Rockefeller University in New York. I loved that job, but two years later my would-be husband wanted to move to Los Angeles for acting work. I didn't really want to move to LA at first, but some members of my family lived there, and after gazing at sunny palm trees in an L.A. webcam for a few months, I grew excited about the journey.

Lucky for me, I soon landed a job at JPL. My primary duty was to help introduce the world to the Spitzer Space Telescope through news releases and web stories and to help with visual forms of storytelling by working closely with imaging specialists at JPL and Caltech. I also helped organize press conferences and pitched Spitzer stories to the media.

Only a month or so after I started the job in the summer of 2003, Spitzer launched into space aboard a rocket that blasted off from NASA's Kennedy Space Center. One of my first assignments was to attend the Spitzer launch and help with media inquiries. In reality, I'm not sure I was much of a help, being so new to Spitzer and NASA launches. But in that swampy place of alligators and space shuttles, I was bitten by the Spitzer bug and was thrilled to learn more.

Gay Hill was another JPL media rep sent out to work on the launch with me. We were both new to NASA launches and wound up lost a few times on the space center grounds; at one point, we found ourselves deep in the Cape Canaveral Air Force base, and security had to escort us out. The trip was probably one of the most memorable of my life, and the launch itself, which took place at night, amounted to the first time I felt the rumble of a rocket in my bones.

After launch, I got busy writing about Spitzer's first science results. I helped put together a press conference at NASA Headquarters, and it was then I learned the NASA media team does not like spectra. One of the first science results involved detecting icy organic molecules in a planet-forming disk of material, a finding made possible by Spitzer's infrared spectrograph, an instrument that splits light up into a rainbow of different wavelengths (the spectrum), revealing the fingerprints of chemicals. I remember a lot of media folks didn't want to show a spectrum at our first press conference, but thanks to the genius of Robert Hurt, Spitzer's imaging specialist, we won them over. Robert knew how to make spectra look pretty, as you can see here. And of course, his space illustrations helped further sell our stories. Check out his artist's concept of a young giant planet, clearing a path through a dusty planet-forming disk.

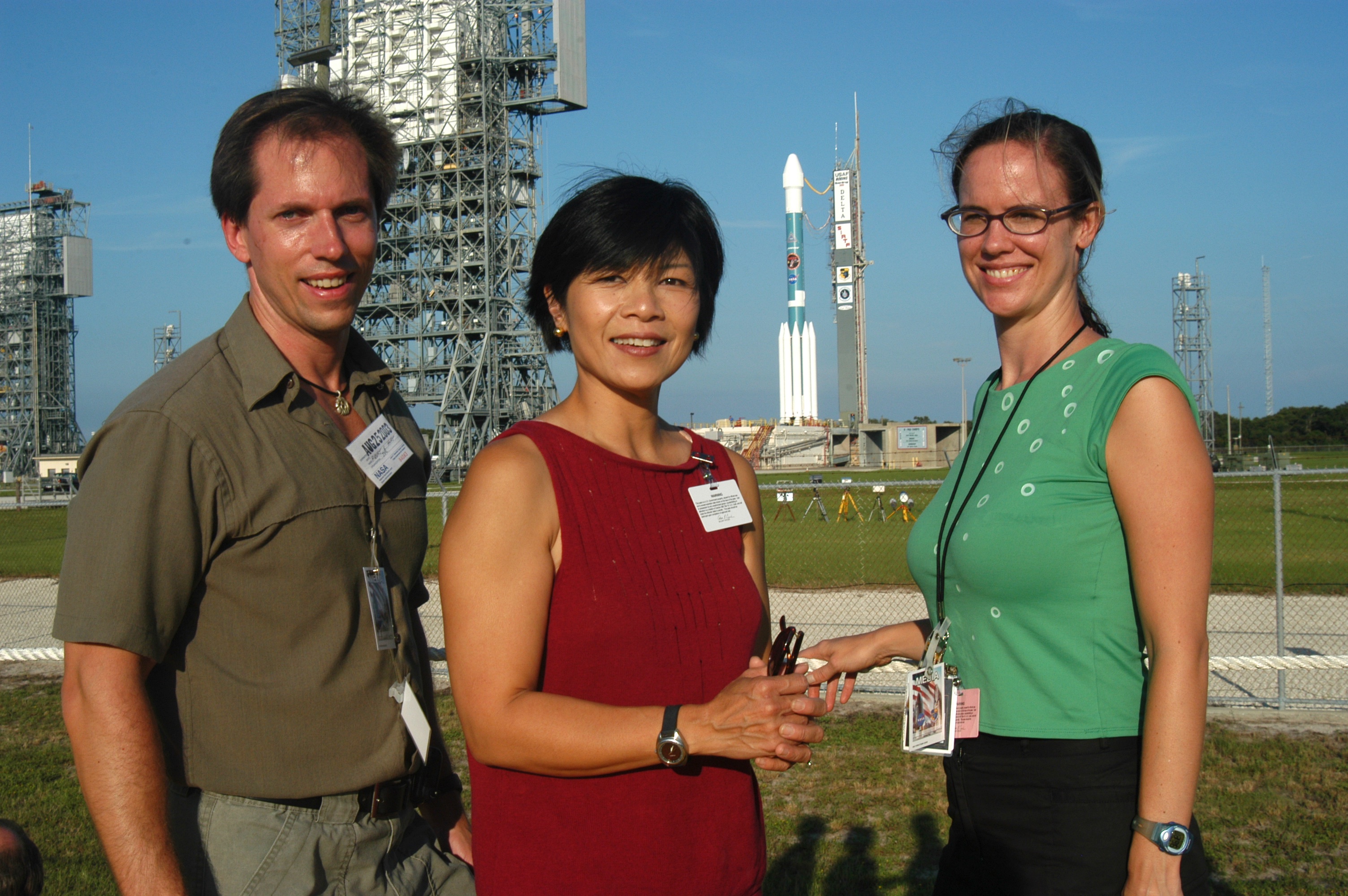

Robert Hurt, Gay Hill, and Whitney Clavin at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center during Spitzer’s launch

One of my favorite parts of working for Spitzer was, in fact, Robert Hurt. Not only did he create our stunning visuals, but he also taught me so much about astronomy. We would talk through every story I wrote, and he would very clearly explain the big picture of why the results were so important and fascinating. He and another Spitzer scientist, Varoujan Gorjian, are my two favorite science explainers of all time! About a year after Spitzer's launch, another artist joined the team, Tim Pyle. I wound up sharing an office with both Tim and Robert for around 10 years. The two of them are my favorite science fiction explainers, who actually convinced me to watch the show “Babylon 5.” To this day, I owe most of my nerd cred to them.

Some of my favorite science results to come out while I worked for Spitzer were the discovery of soccer-ball-shaped "buckyball" molecules in space; and the largest ring around Saturn, a wispy band of ice and dust particles. During my time with Spitzer, the mission also became a trailblazer in the study of exoplanets: it was the first telescope to directly detect light coming from a planet outside our Solar System and would go on to make many other discoveries about the atmospheres of these exotic worlds. Perhaps Spitzer's biggest claim to fame is its discovery of a planetary system with seven rocky planets, called TRAPPIST-1. At the time of that announcement, I had left my job at JPL to start a similar position at Caltech, so, unfortunately, I was not part of the news activities. Robert would tease me about the big news coming up, which would drive me crazy, but when Spitzer finally did release the results to a media frenzy, I felt proud. Spitzer was the "little telescope that could," and I'm happy to have been a small part of its family.

Spitzer's Safe Space: Commanding A Telescope Millions of Miles Away

Spitzer's Safe Space: Commanding A Telescope Millions of Miles Away

Three Months of Checkout, A Lifetime of Memories

Three Months of Checkout, A Lifetime of Memories